I’m currently researching the philosophy of the Presocratic philosopher Anaxagoras for a book I’m writing about Socrates. I’m very interested in the therapeutic dimension of Greek philosophy, particularly Stoicism. So I’ve been wondering if Anaxagoras’ philosophy can potentially be read from that perspective. I’m not suggesting that Anaxagoras was a psychotherapist, or that his philosophy can be reduced to therapeutic techniques, or even that this is necessarily how he intended parts of his philosophy to be received. I’m simply interested in whether ancient followers of his philosophy would have potentially derived psychological benefits from it, and whether some of his ideas could perhaps benefit modern readers in a similar way.

Our evidence for the life and thought of Anaxagoras is fragmentary, obscure at times, and even, prima facie, contradictory — it’s notoriously problematic for modern scholarship. With that caveat in place, I’ll excuse myself for adopting a particular reading of the extant fragments, which I won’t attempt to justify in this article, because my goal here is to focus on exploring possible psychological benefits of the teachings, as they’re handed down to us in the surviving literature. I’ll leave it to others to decide how accurate the resulting account of his life and thought is, although, of course, I’ve attempted to base it on a reasonable interpretation of the available evidence. So how can the philosophy of Anaxagoras actually help us today?

The Life of Anaxagoras

I’ll begin by saying a little about Anaxagoras’ life, for historical context. He was a philosopher from Klazomenai in Ionia, on the Aegean coast of modern-day Turkey. He was probably born around 500 BCE and died around 428 BCE, although these dates are rather uncertain. As a young man, aged around 20, he arrived in Athens, and was, it’s claimed, the first there to actually be called a “philosopher”. He was, indeed, the earliest representative at Athens of the so-called Ionian school. Klazomenai had formerly been controlled by Athens but in 387 BCE it became part of the Persian empire, hence Anaxagoras may have been viewed by some as a Persian subject, or at least a potential sympathizer. As a foreign thinker residing in Athens, he naturally aroused curiosity and suspicion.

Anaxagoras famously stated that the universe was caused by something called Nous, a cosmic intellect which organized matter into the distinct objects of our experience. He placed so much importance on this concept that he earned himself the nickname Nous, which would perhaps be a bit like the public dubbing a well-known intellectual today “Brains” or “The Thinker”, although it was possibly meant in a disparaging sense like “Egghead” or maybe even someone who thinks too much for his own good.

He was, in a sense, a typical intellectual. He was known for being lofty and high-minded. The only book written by him seems to have been concise, and expressed in a pleasant, lucid style. His life was wholly dedicated to the quest for truth, causing him to seem aloof from everyday materialistic concerns. Anaxagoras came from a wealthy and noble family, yet was content to give away his fortune. When his relatives accused him of neglecting his inheritance, he simply replied “Why don’t you look after it then?”, and handed it over to them.

He said “I care greatly for my native land,” as he gazed upwards.

Having migrated to Athens, where he lived as a foreign resident or metic, he focused entirely on his philosophical studies, and therefore remained uninvolved in public life, something many Greeks viewed with suspicion. He was once asked why he believed he had been born, replying “To study the sun, the moon, and the heavens.” He appears to have viewed the goal of life in general as the pursuit of such knowledge. Someone scolded him saying “Do you care nothing for your native land?” He simply pointed at the stars, telling them to hush, and saying “I care greatly for my native land,” as he gazed upwards. If he meant to imply that he considered himself a citizen of the cosmos, he may be seen as foreshadowing the cosmopolitanism of later thinkers, such as Diogenes the Cynic, and the Stoics.

Anaxagoras, like other Ionian philosophers, emphasized naturalistic interpretations of phenomena that Greeks often viewed as supernatural, or of divine origin. He reputedly predicted the fall to earth, in 467 BCE, at Aegospotami on the Hellespont, of a large meteorite, possibly coinciding with the passing of Halley’s comet, from which it may have originated. The meteor was described as a lump of stone, around a “wagonload” in size. Anaxagoras’ association with this event appears to have bolstered his fame considerably. Whether or not he really predicted the date of the meteorite’s impact, he could point to the find as evidence for his controversial claim that celestial bodies were made of something akin to burning stone or iron.

In particular, Anaxagoras became known for teaching his followers that the sun was a blazing lump of stone or iron. He was implying, of course, that the sun was not a divine being, riding a horse-drawn chariot across the sky. At best, such myths were metaphors for natural phenomena. Naturalistic explanations, though, still caused some controversy. Many Athenians were not yet used to, and perhaps not entirely ready for, such radical ideas.

Although Anaxagoras’ whole philosophical method must have ruffled some feathers, it seems his claims about the sun may have been the final straw for his critics. He found himself dangerously at odds with conservative religious elements in Athenian society. The conflict was perhaps especially with regard to the official worship of Helios, the sun god. Helios was a minor deity, in the state religion, primarily associated with harvest festivals, and the cult of Demeter at Eleusis. That said, the sun becomes a “great god”, portrayed as much more important, in the writings of Greek poets and certain philosophers, including Plato. The god Apollo later became identified with the sun, or Helios, but it is doubtful that he typically was during the 5th century, except perhaps in a lost tragedy of Euripides called Phaethon. This play was connected with Anaxagoras by later authors, probably because it tells the story of a young mortal whose attempts to master the sun lead to disaster, and end with him, blasted by Zeus, crashing down to earth by a great river, like a meteorite.

The Trial and Exile

Anaxagoras is believed to have served as a tutor to Pericles, who later became the leading statesman in the Athenian democracy. They must have been good friends. Pericles retained Anaxagoras as an advisor until the philosopher was placed on trial at Athens, around 450 BCE. Anaxagoras was charged with impiety, for claiming the sun is a red-hot lump of iron, and possibly also conspiring with Greece’s enemies, the Persians. If the teacher could be condemned, it would subsequently be easy to argue that his famous student had been corrupted. So it is often assumed that the trial was really an indirect attack on Pericles by his political opponents, either Cleon or Thucydides, son of Melesias (not the famous historian). Pericles had had his main political rival, Cimon, the leading figure of the oligarchic faction, exiled by means of an ostracism vote, ten years earlier. As it happens, Cimon returned to Athens about a year before the charges were brought against Anaxagoras — so we may wonder whether he was somehow involved.

Anaxagoras was found guilty and, according to one account, sentenced to death. Pericles, however, stood before the the court, placing his own reputation on the line, to defend his friend and tutor. He courageously asked the people whether they could find a single thing to criticize in his own conduct. They could not. He said, “Well, I am this man’s student. Do not be carried away by slander, and put him to death, but listen to me and release him.”

Some say, Anaxagoras was brought into court so frail from disease, that the jury took pity upon him. The sentence was reduced to exile, and a fine of five talents, a small fortune. One talent was enough silver to pay the crew of a trireme for a month. Pericles may have paid the fine on Anaxagoras’ behalf, if it’s true he’d given away his own inheritance

Anaxagoras spent his remaining years exiled in Lampsacus, a Greek city on the eastern side of the Hellespont. It happens to face the very spot, at Aegospotami, where the meteorite had fallen about seventeen years earlier. The people of Lampsacus held Anaxagoras in very high regard, although the public indignity of his trial and banishment reputedly left him a broken man. His friend Pericles would eventually die of the plague at Athens, in 429 BCE. Anaxagoras passed away the following year, by suicide according to some. Diogenes Laertius, seven centuries later, would therefore write:

The sun’s a molten mass,

Quoth Anaxagoras;

This is his crime, his life must pay the price.

Pericles from that fate

Rescued his friend too late;

His spirit crushed, by his own hand he dies.

Socrates and Anaxagoras

Curiously, Socrates, who was known for seeking out the greatest intellectuals of his era, seems never to have met Anaxagoras, the man who, only a generation earlier, had founded the study of philosophy at Athens. Socrates must have been around twenty years old when Anaxagoras, aged around fifty, stood trial. He may already have been dabbling in the study of philosophy for up to five years.

It’s natural for us to imagine that Socrates would have loved nothing more than to have spoken with Anaxagoras and yet for some reason was unable to do so. The most obvious explanation would be that, in his youth, Socrates lacked the social connections who may have introduced him to Pericles’ intellectual circle. (Perhaps Anaxagoras charged hefty fees, which Socrates could not afford, although this would clash with the former’s portrayal as a man indifferent to wealth.) In a sense, though, Socrates spent the rest of his life making up for this missed opportunity, by mingling with most of the other great minds of Athens, including the famous tragedian Euripides, who had, like Pericles, been a student of Anaxagoras.

Ironically, then, it may have been the very attempt to censor Anaxagoras that finally placed his teachings in the hands of Socrates and countless other young Athenians.

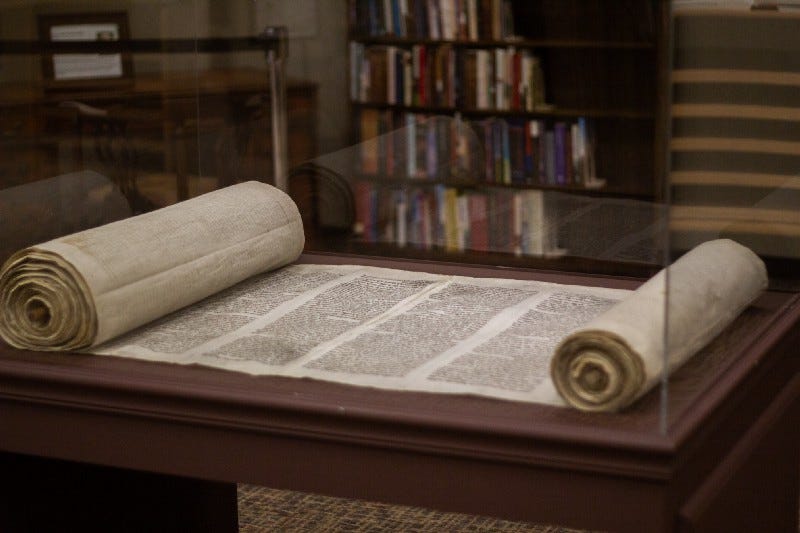

After the trial, Socrates became a student of Anaxagoras’ successor at Athens, Archelaus, who was probably the first Athenian citizen to teach natural philosophy at Athens. He seems to have read to Socrates from a copy of the only book written by Anaxagoras. The little book of Anaxagoras later became widely available, and we’re told it could be purchased, in the Agora, for only a single drachma. Clearly, those who sought to “cancel” Anaxagoras, for impiety, had completely failed to suppress his writings. One possibility is that Anaxagoras had circulated this text privately among his friends and students at first but after his exile, once he was gone and could no longer be held responsible or control the publication of his writings, cheap copies became more freely available. Ironically, then, it may have been the very attempt to censor Anaxagoras that finally placed his teachings in the hands of Socrates and countless other young Athenians.

Socrates was, as a young man, fascinated by natural philosophy. However, he eventually became frustrated with the explanations it offered of natural phenomena. When he learned that Anaxagoras had made Nous, or Intellect, the cause of the universe, Socrates was exhilarated because it seemed to promise a more profound level of philosophical analysis. Minds have intentions, which Socrates hoped to study and understand. Socrates therefore wanted to know more about what this cosmic Nous actually was. However, his joy soon turned to disappointed, when he discovered that Anaxagoras made quite superficial use of this concept, and offered little explanation of its meaning. Nous, which explains everything for Anaxagoras, is itself explained by nothing. This initial frustration perhaps fuelled Socrates’ later insistence on the most important concepts in an argument being clearly defined from the outset.

Socrates, it seems, assumed that, being goal-directed or “teleological” in nature, cosmic Nous must have some plan for the world. In order to understand nature, therefore, we would have to understand what Nous considered the best arrangement of things. Anaxagoras was little help in this regard and Socrates realized that trying to analyze the real nature of things in terms of Nous would simply end in speculation. As a result of this dead end, he gradually abandoned the study of natural philosophy in favour of a new approach, which focused primarily on studying human nature, ethics, and what is best for man, i.e., the virtues.

Socrates was therefore critical of Anaxagoras’ philosophy, and sought to distance himself from his teachings, which he was accused, in his own trial for impiety, of repeating. Nevertheless, he also seems to have admired Anaxagoras, and to have been influenced by him in certain ways. There are such obvious parallels between the two philosophers’ lives that it’s difficult to imagine that Socrates did not feel as though he was walking, at times, in the footsteps of his ill-fated predecessor.

For instance, in Aristophanes’ satire The Clouds, first performed in 423 BCE, five years after the death of Anaxagoras, Socrates is pilloried as a natural philosopher, running a school called the Phrontisterion, “Thinkery” or “Thinking Shop”, and in the Symposium of Xenophon, an angry man is therefore shown disparaging Socrates as the Phrontistes, “The Thinker”. These inevitably remind us of Anaxagoras’ nickname of Nous, the archetypal intellectual or thinker, in the eyes of contemporary Athenians. Socrates took Anaxagoras’ place as Athens’ foremost philosopher, but he was a very different sort of thinker, who placed more importance on asking the right question than speculating about the answers, who didn’t present himself as an “expert”, and who was more interested in human nature than the nature of celestial phenomena.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.