"You slip in, Zeno, by the garden door — I'm quite aware of it — you filch my doctrines and give them a Phoenician make-up."

This intriguing remark was reportedly made by Polemo of Athens, the head of the Platonic Academy. He is accusing Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, of pinching ideas from his philosophy. Stoicism was perceived by some Greeks as having originally borrowed certain doctrines from Platonism, a native Athenian philosophy, and dressed them up in a more Phoenician style. We’re left, though, to puzzle over precisely what this meant.

It’s often said that Stoicism was a school of ancient Greek philosophy but this isn’t entirely accurate.

It’s often said that Stoicism was a school of ancient Greek philosophy but this isn’t entirely accurate. It was “Greek” to the extent that it was founded at Athens, and taught, as far as we know, exclusively, in the Greek language. (At least until Cicero began to translate Stoic philosophy into Latin, two and a half centuries later.) However, most of its early luminaries, came to Athens from several regions of West Asia (Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, and the Levant). Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, is repeatedly described not as Greek but as Phoenician. Athenians, of that period, indeed, saw the philosophy as somewhat foreign.

Zeno, the son of Mnaseas (or Demeas), was a native of Citium in Cyprus, a Greek city which had received Phoenician settlers. — Diogenes Laertius

As we’ll see, other references make it clear that Zeno was related to these Phoenician settlers rather than to the original Greek colonists. After being conquered by Alexander the Great, in 333 BCE, around the time when Zeno was born, Cyprus was progressively Hellenized. (The term we use to refer to a foreign nation embracing Greek language and culture.) Nevertheless, Cyprus still retained ties to Phoenician culture:

Citium in Cyprus, the native place of Zeno, had a population which was largely Phoenician in blood. It was ruled by a dynasty of Phoenician petty kings, whose names figure in the Punic inscriptions found on the spot From 361 to 312 B.C., within which period the first twenty years of Zeno's life probably fall, its king was Pumi-yathon the son of Milk-yathon the son of Baal-ram. — Edwyn Bevan, Stoics and Sceptics

The evidence of inscriptions therefore suggests that a Phoenician royal dynasty continued to rule Citium throughout Zeno’s youth, until around the time he left and ended up in Athens.

What of his father’s name, mentioned in the quote above? Jacques Brunschwig, a professor of Ancient Philosophy at the Sorbonne, writes in a recent study of Zeno’s origins:

It is generally agreed that Mnaseas is a hellenized version of Semitic names like Manasse or Menahem. If that is true, the conclusion to draw would be, of course, that Zeno’s father was a Phoenician; but also, and much more importantly in my opinion, that he was already a hellenized Phoenician.

Zeno’s own name, as Brunschwig notes, is thoroughly Greek. Rather appropriately for the founder of Stoicism, it means “[born] of Zeus”. Mnaseas, his father, was perhaps born into a family who identified more with their Phoenician heritage, and lived to see the Hellenization of Cyprus. Zeno, his son, was probably born into a culture at Citium, which was already becoming Hellenized, despite still being governed by Phoenician nobles. Diogenes Laertius makes a point of describing him as melanchrous, however, which means black-skinned or swarthy. (Ancient sailors were typically described as swarthy from being exposed to the sun on the decks of their ships.) The point he’s trying to make seems to have been that Zeno was somewhat darker in appearance than a typical Athenian. Basically, to most Greeks, he looked foreign.

Who were the Phoenicians?

The Phoenicians, in the eyes of Athenians, were a seafaring race of barbarians. (The derogatory term barbaroi literally meant people who sound like they are saying bar bar or blah blah, i.e., who speak a foreign tongue.) Crucially, that is, they were not Greek. They are now believed to have been a Semitic people, possibly related to the Canaanites, who originated in the Levant region of West Asia. Some scholars have questioned whether the Phoenicians actually existed as a distinct civilization. It may just have been a term used by the Greeks to lump together various seafaring semitic peoples who shared a common language. Nevertheless, in the eyes of Greeks, the Phoenicians constituted an ancient barbarian nation, which had been conquered and was ruled by Persia, and became part of the Seleucid Empire during the Hellenistic Era, although the Phoenician cities always retained a considerable amount of autonomy.

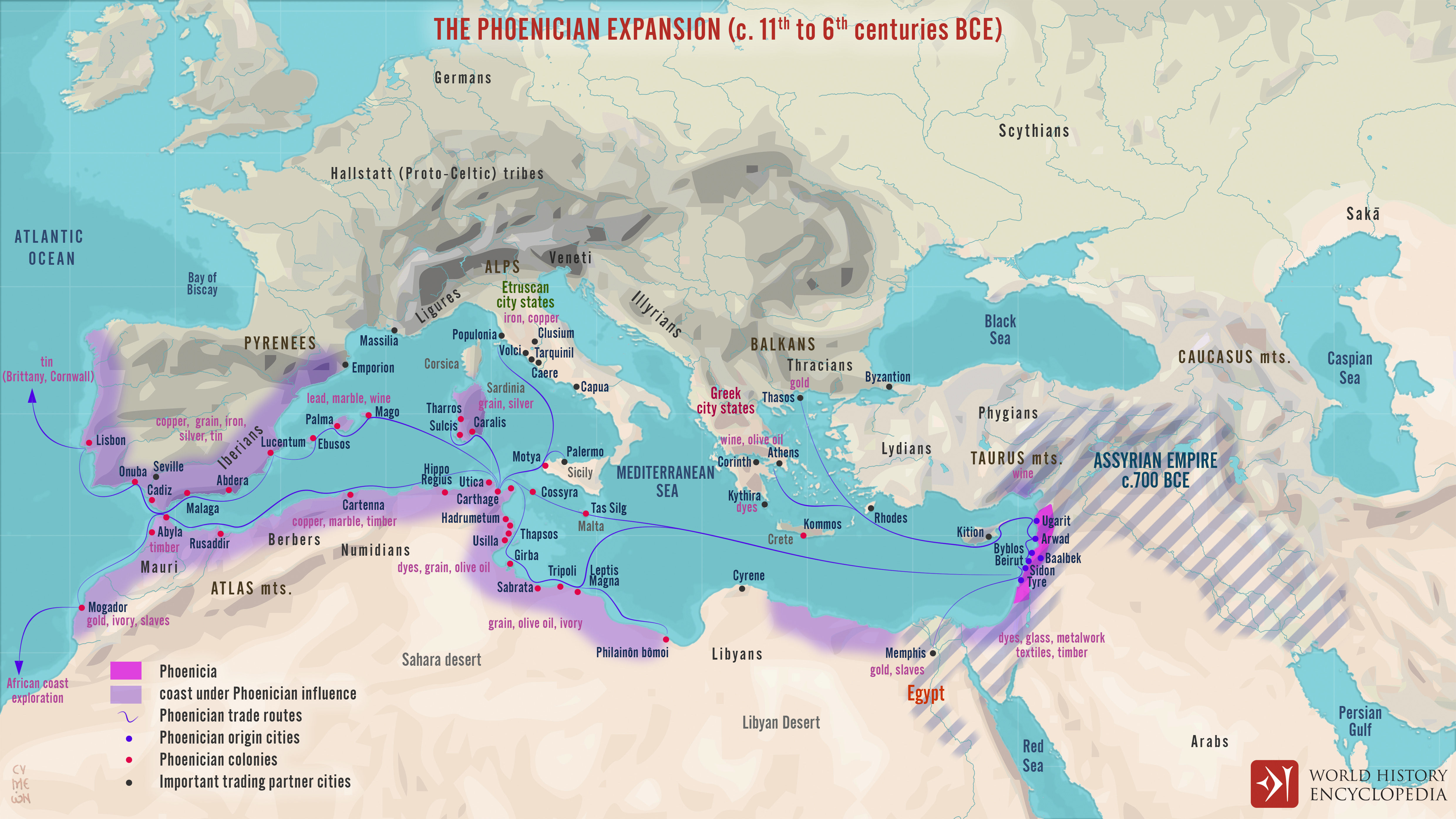

As far as we know, Phoenicia never had a centralized government but was always a loose federation of city-states. In this regard, it was not unlike ancient Greece. Tyre and Sidon were originally the two most prominent Phoenician cities — both located in modern-day Lebanon. As result of their success as seafaring merchants, the Phoenicians spread throughout the Mediterranean, settling along the north coast of Africa as far west as Spain. They are even believed to have traded with the ancient Britons. They were renowned as master shipbuilders and Phoenician had one of the earliest written alphabets. According to Greek legend, the Phoenician hero Cadmus, prince of Tyre, founded Thebes. The historian, Herodotus, claimed that Cadmus introduced the Phoenician alphabet to Greece, which led to the evolution of written Greek. Europa, the daughter of Cadmus, according to Greek mythology, was abducted by Zeus, who took the form of a bull. She settled in Crete where she gave birth to King Minos, and founded the Minoan civilization.

Phoenicia therefore once constituted a powerful thalassocracy, or maritime empire. They were traditionally allied with, and provided ships for, Persia, the most powerful “barbarian” enemy of Greece. In Zeno’s time, following the conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great, however, the heartland of Phoenicia, in the Levant, became part of the Hellenistic successor state known as the Seleucid Empire. Cyprus became part of the Ptolemaic Empire, a rival Hellenistic successor state, governed from the city of Alexandria, in Egypt.

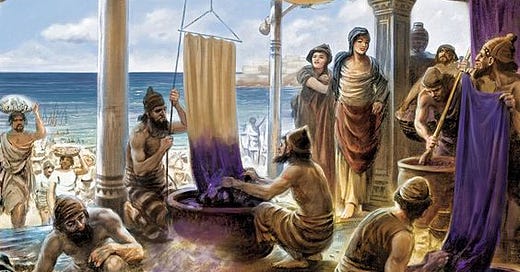

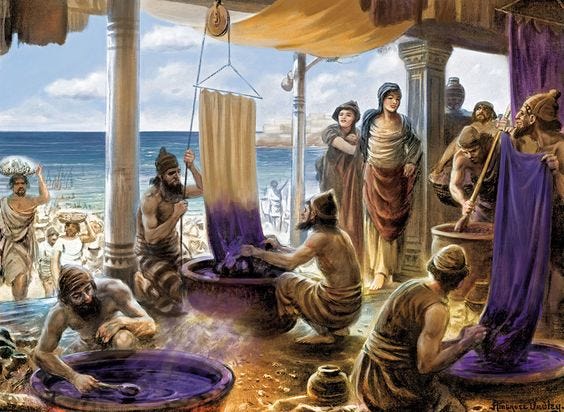

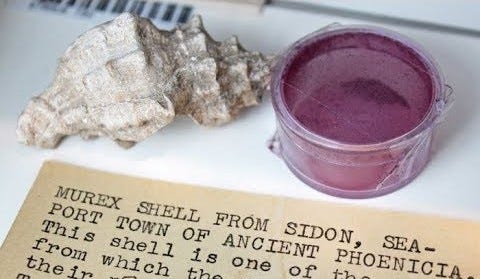

The Phoenician civilization was built upon maritime trade and they were particularly known for manufacturing and trading the most precious dye of the ancient world, known as Tyrian purple. Indeed, the name Phoenicia, given to them by the Greeks, appears to be related to the word phoinix (“purple”) and perhaps meant “the purple people”. (We do not know what these people actually called themselves.) Slaves painstakingly extracted a tiny quantity at a time from the innards of fermented murex sea snails. It was one of the most unpleasant jobs in the ancient world but the resulting dye could be worth its own weight in silver.

Zeno himself was a seafaring dye merchant, who probably travelled between Cyprus, the Levant, and various Greek cities, including Piraeus, the port of Athens.

He [Zeno] was shipwrecked on a voyage from Phoenicia to Piraeus with a cargo of purple. — Diogenes Laertius

After being shipwrecked near Athens, Zeno settled there, living as a metic or foreign resident, which meant he had limited rights compared to an Athenian citizen. For instance, he was most likely prohibited from owning property within the city of Athens. (He may have lodged with friends.)

Another anecdote, attributed to the contemporary writer, Antigonus of Carystus, seems intended to highlight that Zeno could potentially have passed for a Greek, despite his dark complexion, as he had been brought up to be familiar with the language and culture. He earned respect for continuing to be transparent about his Cypriote birthplace.

[…] he never denied that he was a citizen of Citium. For when he was one of those who contributed to the restoration of the baths and his name was inscribed upon the pillar as "Zeno the philosopher," he requested that the words "of Citium" should be added. — Diogenes Laertius

He was clearly proud of being a Cypriote but this story implies that it was something he might have been tempted to conceal. He probably risked being looked down upon as a “barbarian” because of his Phoenician ancestry.

After his death, decades later, he was highly-honored in Athens. A statue of him was erected in Citium, and his legacy was also celebrated by the Phoenician community in Sidon.

The people of Athens held Zeno in high honour, as is proved by their depositing with him the keys of the city walls, and their honouring him with a golden crown and a bronze statue. This last mark of respect was also shown to him by citizens of his native town, who deemed his statue an ornament to their city, and the men of Citium living in Sidon were also proud to claim him for their own.

This final remark is ambiguous but may refer to Phoenicians who had migrated from Citium to Sidon and viewed Zeno as part of their community. Perhaps Zeno’s family were originally from Sidon, and he still maintained a connection with relatives there. It is likely that, as a seafaring merchant, Zeno would have sailed between his home city of Citium, in Cyprus, and the major Phoenician city of Sidon, in the Levant. In any case, Zeno’s kinship with inhabitants of Sidon reinforces the image of him as a Phoenician.

There’s an obvious sense in which the Phoenician dye trade made an impression on Stoicism. There are many references to seafaring, trade, and dye, used as metaphors in Stoic philosophy. The most famous come from the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, written nearly five centuries after Zeno was shipwrecked at Athens. For example, he tells himself to remember that his imperial (Tyrian) purple robe is merely “some sheep's wool dyed with the blood of a shellfish”, and of no real intrinsic value (Meditations, 6.13).

The Foreignness of Stoicism

The foreignness of Stoicism, its otherness to the Athenians and other Greeks, is clear from the way that “Phoenician” appears to be used in a somewhat derogatory way by ancient authors to refer to the philosophy. According to Diogenes Laertius, Crates of Thebes, the Cynic, referred to Zeno, who became his student, as “my little Phoenician”.

"Why run away, my little Phoenician?" quoth Crates, "nothing terrible has befallen you." — Diogenes Laertius

The term Phoinikidion (“little Phoenician”) could be affectionate but here seems to be moderately derogatory — not unlike how you’d expect to hear an Athenian refer to a “barbarian” slave. In general, though, using language in this way to downplay, or level, the importance of people and things was quite typical of Cynicism.

Cicero, writing three centuries before Diogenes Laertius, however, uses a similar phrase in Latin, referring to Zeno as “your little Phoenician” (in a fictional dialogue where the Stoic Cato is being addressed). He stresses that the inhabitants of Citium “originally came from Phoenicia”, as we’ve seen, and refers to Zeno as exhibiting the “cunning” supposedly typical of his Phoenician race.

Diogenes Laertius also quotes a satirical poem about Zeno, by his contemporary Timon of Phlius, which begins:

A Phoenician too I saw, a pampered old woman ensconced in gloomy pride.

A later Stoic, Zenodotus, wrote apologetically of Zeno’s Phoenician birth (portraying him not in effeminate but manly terms):

Thou madest self-sufficiency thy rule,

Eschewing haughty wealth, O godlike Zeno,

With aspect grave and hoary brow serene.A manly doctrine thine: and by thy prudence

With much toil thou didst found a great new school,

Chaste parent of unfearing liberty.And if thy native country was Phoenicia,

What need to slight thee? came not Cadmus thence,

Who gave to Greece her books and art of writing? — Italics added

His point is that Greeks should not be prejudiced against Zeno for being Phoenician. He compares him to Cadmus one of the greatest heroes of Greek mythology, and the founder of Thebes, who happened to be a Phoenician prince and came originally from the city of Tyre — so not all Phoenicians are bad!

It seems clear from these references in Cicero and Diogenes Laertius, the latter reputedly quoting much earlier sources such as Crates, Timon, and Zenodotus, that the founder of Stoicism was viewed very much as a foreigner. He, and the philosophy he founded, appear to have been looked down upon by some Greeks for this reason. Stoicism was, to some extent, originally seen as a Phoenician and therefore, technically, a barbarian or non-Greek philosophy. We have even seen Zeno being criticized due to Greek (and Roman) prejudices toward the Phoenician race, and defended against the same prejudices by his followers.

Perhaps it would be most accurate to say that Stoicism was originally viewed very much as a Hellenistic philosophy, founded by a Phoenician metic (or immigrant) at Athens, expressed in the Greek language, but (somehow) showing signs of foreign influence, which distinguished it from the Platonism of Polemo’s Academy, and other established branches of Greek philosophy. In short, it was not really a native Greek philosophy in the sense that Platonism and Aristotelianism were. There was originally something slightly alien about the Stoic world-view, perhaps not unlike the presocratic philosophies which had come to Athens from Ionia over a century before Zeno’s time.

It’s also noteworthy that although the Stoic school was based in Athens, most of its subsequent leaders (scholarchs) came from overseas, particularly cities of Asia Minor and the Levant, including Sidon and Tyre, as well as the island of Rhodes, where Phoenicians had settled. (See the partial list on this interactive map.) At least six of the most famous Stoics of the Hellenistic era, in fact, came from the city of Tarsus, or its vicinity, the capital of Cilicia, which was another important centre for maritime trade where the Phoenicians had settled. Tarsus, which was said to have one of the greatest libraries of the ancient world, seems to have had a particularly strong association with Stoic philosophy. A century after Panaetius, the last Stoic scholarch died, Saint Paul was born in the city of Tarsus — Paul was originally known as Saul of Tarsus. Some scholars find traces of Stoicism in his writings.

Of course the resemblance between Zeno, the Hellenized Phoenician of Citium, and Paul, the Hellenized Hebrew of Tarsus, is not purely accidental. The author of the Acts has assuredly put into the mouth of his Paul, with deliberate purpose, phrases characteristic of the teaching which went back to Zeno. Nor is the connection made by the writer an arbitrary one; it is the index of a great fact — the actual connection in history between Stoicism and Christianity. Looking back, we can see more fully than was possible at the moment when the Acts was written, to what an extent the Stoic teaching had prepared the ground in the Mediterranean lands for the Christian, what large elements of the Stoic tradition were destined to be taken up into Christianity. — Edwyn Bevan, Stoics and Sceptics

Conclusions and Questions

What ideas was Polemo accusing Zeno of pinching? It’s easy to see the influence of the Platonic Academy in early Stoic thought. What could he possibly have meant, though, by saying that Zeno dressed up bits of Platonic philosophy to give them a more Phoenician appearance? As Brunschwig notes:

One would pay much to know what Polemo meant by this "Phoenician makeup": was it a matter of philosophical doctrine, or a matter of expression, style and vocabulary?

An easy answer would have been that Zeno translated Platonic ideas into the Phoenician language but Zeno only ever taught in Greek as far as we know. In De Finibus, Cicero levels a similar criticism at the Stoics for merely rehashing ideas of Platonism in different (Greek) terminology. It’s far from clear how this Stoic philosophical jargon could be described as “Phoenician”, though.

Perhaps there’s another way in which Zeno’s Stoicism may have appeared “Phoenician” to the Greeks. Stoic teachings were divided into three broad topics: ethics, physics and logic. It seems difficult to imagine how Zeno could have dressed Academic logic up in a Phoenician style. Stoic ethics resembled that of Polemo but was more austere, apparently under the influence of Cynic philosophy. It’s difficult to imagine how Zeno’s ethics, therefore, could be described as Phoenician in appearance. My best guess is therefore that Polemo meant Zeno’s physics somehow came across as Phoenician.

The main characteristic of early Stoic physics was that it was pantheistic and influenced by the presocratic philosophers known as the Ionians. Plato identified the divine with the transcendent realm described by his famous Theory of Forms. The Stoics completely rejected this metaphysical view and instead identified their God with the universe considered as a whole, which they considered to be a rational living being, called Zeus. We know very little about the theology of the Phoenicians but they appear to have followed a form of the Canaanite religion, which worshiped the semitic god Baal, typically represented by the image of a bull. (The image of the bull also occurs in the symbolism of Stoic philosophy, e.g., Epictetus appears to compare the Sage to a bull, and Zeno compared the ideal republic to a herd of cattle.) He was known by Phoenicians as Baal Shamen or Lord of the Heavens, and worshipped as a storm god, representing life and fertility, sometimes equated with the Greek god Zeus. The Canaanite religion, however, appears to have been polytheistic rather than pantheistic.

Stoic physics drew on the work of Ionian philosophers, such as Heraclitus, who were known for their pantheism. Although the Ionians were Greeks, they lived in colonies on the coast of Asia Minor, under Persian rule until the start of the fifth century. In Ionia, therefore, Greek culture mingled with influences from Persia and Phoenicia. Moreover, the historian Herodotus claimed that Thales, the founder of Ionian philosopher, though born in the Ionian city of Miletus, was, like Zeno, a Phoenician. “Thales a man of Miletus,” he calls him, “who was by descent of Phoenician race.” Diogenes Laertius later expands upon this, writing, “Herodotus, Duris, and Democritus are agreed that Thales […] belonged to the Thelidae who are Phoenicians, and among the noblest of the descendants of Cadmus and Agenor.” According to this account, therefore, Thales came from a family of Phoenician nobles. Other accounts refer to Thales as Greek, so it’s likely he was a Milesian citizen with some Phoenician blood in his family.

Unfortunately, we know relatively little about Thales’ philosophy, and there are no direct links with Zeno’s Stoicism. However, some scholars consider him to have been a monist, and a sort of pantheist. The Ionian philosophers who came after him were certainly associated with pantheism and, as we’ve seen, in the case of Heraclitus, there seems to be a clear influence on Stoicism.

These observations are, sadly, inconclusive. We’re left with some questions. Could the Phoenician appearance of Stoicism somehow have been due to the unique jargon that it used after all? Could Polemo somehow have been referring to the influence of Phoenician religion, the worship of Baal, on Stoic theology, and their distinct conception of Zeus? Or could the influence on Stoic physics of Ionian philosophy, founded by the Phoenician Thales, with its emphasis on monism and pantheism, have been perceived as sufficiently Phoenician to justify the remark? Perhaps we’ll never know for sure but I hope these reflections might inspire someone else to spot a connection, which could shed further light on the origins of Stoicism, and perhaps thereby the meaning of some of its more obscure concepts.

So Zeno's critics were possibly 'zeno'-phobic! 🤭

Very interesting history. I had no idea the Phoenicians were considered a Semitic people and were possibly descendants of the Canaanites? That bit about St. Paul was fascinating as well. Thanks for the history lesson, Prof! 😃