Coping with your Emotions

What to actually do when you notice you're getting upset

In this article, I’m going to describe in plain language how I advise people to cope with anxiety, anger, sadness, and other troubling emotions.

Most of the coaching that I currently do draws on the Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT) of Albert Ellis, as well as elements of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and other modern evidence-based therapies. However, I use a version of Aaron T. Beck’s AWARE acronym, from Cognitive Therapy, to summarize my advice about coping with certain emotions, as I find that can make the steps easier to remember.

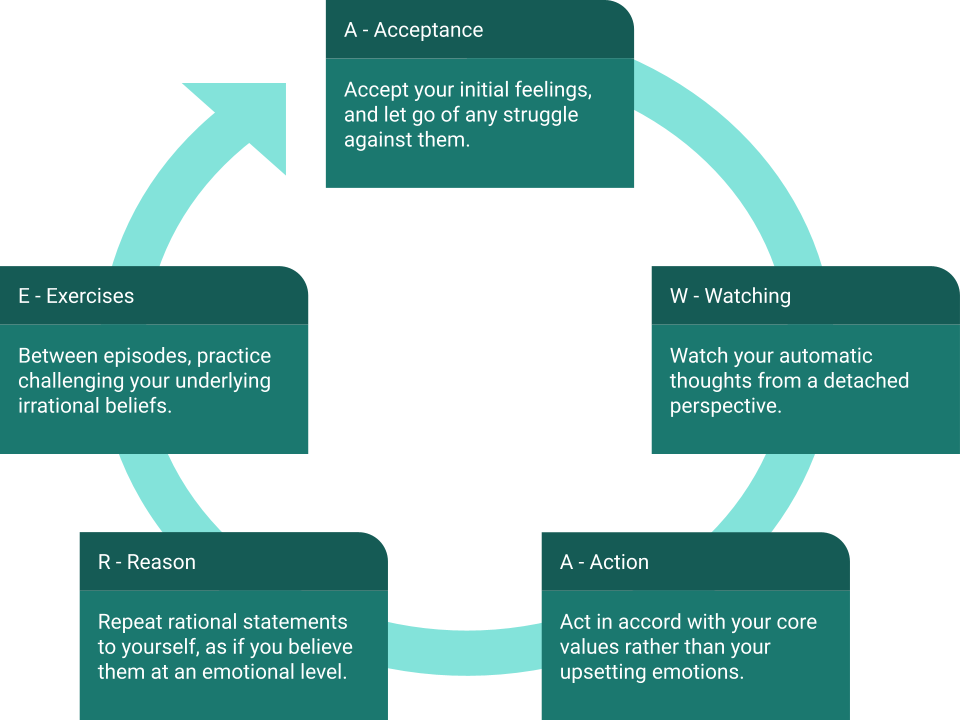

A = Accept your Feelings

W = Watch your Thoughts

A = Act in Accord with your Values

R = Repeat Rational Statements

E = Exercise Between Episodes

I suggest that, to get started, you give yourself “self-instructions”, as if coaching yourself verbally, in your mind, through various changes in attitude, attention, and behaviour. For example: “Slow down, pause, notice your anger”, etc. Over time, however, you’ll be able to abbreviate these instructions, and finally abandon most of them. Self-talk works best as a temporary stepping-stone until, through practice, you’ve completely internalized your own guidance and the coping skills it describes have become second nature. In particular, you will probably find that in a stressful situation it can overload your brain if you try to give yourself too many verbal instructions at once.

So begin, very simply, by coaching yourself through the acceptance part below. Next, perhaps after several days, shift the emphasis to watching your thoughts. Once you’ve made some more progress, begin repeating a rational coping statement. That’s the most systematic way to proceed but you can also pick the instructions you find most helpful and just focus on those for a while. Remember, consistency is the goal rather than perfection. You will gain both skill and confidence with practice.

Five Ways to be AWARE

A = Accept your Feelings

Most people blur the distinction between their initial automatic feelings and the layers of feelings that they create in response. We very often get second-order distress by making ourselves upset about getting upset. You may get anxious about your anxiety, sadness, or anger; sad about your sadness, anxiety, or anger; angry about your anger, anxiety, or sadness, and so on, piling pain on top of pain. Second order distress not only adds another layer to our initial suffering, it often prevents the original feelings from running their course naturally, and fading over time — getting upset with yourself in this way, in other words, can lock your painful emotions in place and perpetuate them indefinitely.

So look out for the earliest signs of anxiety or other emotions and accept the initial surge of feeling without adding to it. Peel back the label “ANXIETY”, “SADNESS”, “ANGER”, or whatever you call it, and look long and hard at the raw sensations underneath — perhaps your heart is beating faster than normal, or some tension in your muscles. Often these are sensations you experience in other contexts — such as during exercise or when overjoyed — without any suffering at all. View these raw sensations as natural and harmless, therefore, and allow them to come and go freely. The struggle just makes you tense up — but you’re battling against yourself. By accepting your feelings and letting go of any struggle against them, ironically, you’ll find they become less of a problem. Your brain will be able to process them naturally and move on in its own time. Feelings seldom remain the same — they’re transient and dynamic. Your initial surge of emotion will usually abate naturally, if you stop fighting to control or avoid it. So grasp the nettle and consciously decide to sit with your painful feelings for longer than normal.

Many people report that it helps to consciously tell themselves to slow down, pause, and wait for their feelings to run their course. You can literally tell yourself: “Stop”, “Wait”, “Slow down”, “Just a minute” — to buy yourself time. Sometimes this is called: Stop and Think. It only takes a few moments to shift the balance back in your favour. At first, you may also find it helpful to say to yourself: “I notice anger”, “I feel anxiety”, “This is sadness emerging”, etc. This is called “affect labelling” — just naming the feeling without evaluation — and many people find it surprisingly helpful.

If you have enough mental bandwidth, and want to go further, you could try saying “Right now, I am aware of tensing my shoulders” or “Right now, I am aware of my heart beating a little faster”, saying these words slowly to ground your attention for longer than normal in your bodily sensations at a more granular level. Doing this helps to shift your brain’s activity away from being dominated by emotional circuits, such as what neuroscientists call the FEAR, RAGE, or GRIEF systems, and toward executive control, and the prefrontal cortex — the part of the brain designed for rational problem-solving.

Some people find it helps to take a deep breath, and to let go of some tension — just introducing more of a pause, without trying too hard to relax. Over time, you will probably find you can slow down, pause, shift your awareness onto your feelings, accept them completely, and so on, without having to give yourself explicit verbal instructions. If you’re really feeling overwhelmed, just focus on this initial stage, and come back to the rest of the AWARE acronym later. You will find, however, that as you get better and more consistent at shifting your attention onto your feelings and accepting them for longer than normal, it becomes much easier for you to observe your own thoughts impartially.

W = Watch your Thoughts

Accepting your feelings is very important but it’s also necessary to detach from unhelpful thoughts and attitudes. The first step is to notice what they are. You may be very conscious of certain words or sentences flashing through your mind — we call these negative automatic thoughts. In many cases, though, you’ll have to infer what your underlying thoughts are in the situation. That’s often obvious from your feelings and actions. For instance, you may be acting as if you believe the situation is extremely bad or dangerous or as if you’re harshly blaming yourself or someone else. You will often notice that the more intense your feelings are, the more rigid and extreme your thinking tends to become. The first step in becoming aware of your thoughts, if they are not already consciously verbalized, is to put them into words. During an episode of strong emotion, you’ll typically have limited time and mental bandwidth available, so don’t overthink this, but do try to articulate what it feels as if you’re thinking.

Observe your thought in real-time, as they happen, almost as if you’re observing someone else’s thoughts. You can help yourself do this by slowing them down or repeating them in a sing-song voice or a different accent. When you’re ready, or if it seems helpful, you can do this instead of giving yourself instructions to accept your feelings. Moreover, if you have the time, you can say to yourself “Right now, I am having the thought ‘________’”, and then name the thought. View it as if you’re placing it inside scare quotes or as if you’re writing it down on a piece of paper, in your mind. The key to accepting upsetting thoughts without buying into them, is to shift perspective in this way, as if you’re looking at them from a different angle, with a sense of curiosity and detachment.

A = Act in Accord with your Values

At first, the best advice is usually to do nothing, except wait, in most situations where you experience unhealthy emotions. The biggest step is abandoning unhealthy coping strategies such as avoidance, seeking reassurance from others, rumination or worrying, venting, and so on. Don’t do anything that’s going to cause more problems, in other words. Just buy yourself time, while you focus on accepting your feelings and watching your thoughts with detachment. If there’s a real problem, and it isn’t absolutely urgent, you will often find it’s better to defer trying to think of a solution until later when your feelings have naturally abated, and you’re able to think more calmly and rationally — as in “worry postponement”. Likewise, if you’re getting upset with another person, it’s often best to take a “time out” until you’ve regained your composure, before deciding what to say to them. Even the most “assertive” words can come across as aggressive if said through gritted teeth, while emotions are still heated.

Ultimately, though, it’s useful to consider acting in a way that’s in accord with your core character-based values (aka “virtues”) rather than driven by how you feel. For many people, one of the most fundamental changes comes simply by realizing that just because you feel like doing something, it doesn’t mean you have to actually do it. When you feel anxious, you may have a powerful urge to flee the situation, for instance. If you value resilience, though, acting in accord with that may mean staying in the situation for longer. When people practice sitting with a feeling without doing what it seems to be demanding — like having an itch without scratching it — therapists call that “urge surfing”.

Here are some things you’re usually best to quit doing:

Avoiding unpleasant situations, procrastinating or putting them off, in a way that creates more problems than it solves.

Ruminating about the past trying to “understand what it means” or “learn something” in order to “fix” your problems

Worrying about the future and circular “What if this happens” / “How will I cope?” thinking.

Venting, complaining, arguing, or going on about your problems too much to other people.

Over-preparing for tasks, in a way that’s unhelpful and driven by anxiety.

Compulsive reassurance-seeking, which doesn’t solve your problems and makes you feel temporarily better but keeps your distress alive for longer.

Self-flagellation, self-criticism, beating yourself up, or giving yourself a hard time, in a way that’s meant to motivate self-improvement but actually does the opposite in the long-run.

Distraction, diversion, using drugs or alcohol, or pornography, in ways that temporarily relieve distress but don’t ultimately help you learn how to cope with your feelings or solve real problems.

Facing your fears and linking your actions to your core values has many psychological benefits, although it can take a little effort to adopt this perspective at first. It can also be helpful to think about the longer-term consequences of your actions. If you have the mental bandwidth available, you could ask yourself: “How will this work out for me?”, “Will I regret this later?” or “What would someone I admire do in this situation?” Notice that you don’t always have to be able to answer these questions. Simply asking them involves shifting your attention in a way that will tend to change the balance of your emotions, buy you more time, and allow you to bring your rational mode of thinking back to the fore.

R = Repeat Rational Statements

When your emotions are strong, focus on acceptance and observation. Over time, by practising the steps above, you will probably find that you are able to catch emotions earlier, improve your self-awareness, sit with your feelings, notice your thoughts, and introduce more of a pause between stimulus and response. When your emotions have settled, you’ll be in a much better position to dispute unhelpful ways of thinking and challenge your underlying irrational beliefs.

When you’re ready, therefore, you may want to begin repeating a rational coping statement, derived from disputation exercises you’ve been doing between experiencing episodes of strong emotion (see below). Keep accepting your feelings and observing your negative thoughts and attitudes but, by this stage, you may find it easier to drop the self-instructions we mentioned above. Just focus on adopting the rational beliefs that are most relevant to your situation. For example:

“I really prefer it when people do what I want, but I don’t NEED them to do so.”

“This may be highly inconvenient but it’s not AWFUL.”

“I can accept myself as fallible; if I sometimes make mistakes, it doesn’t mean I’m a FAILURE.”

“This may be difficult and unpleasant but it’s not UNBEARABLE; I can cope”, and so on.

Repeat your self-statement about three times, as if you really believe it at an emotional level, and try to think, feel, and act as if that’s the type of person you are now becoming in these sorts of situations, and in life generally.

E = Exercise between Episodes

You can describe the steps above as reactive coping strategies, meaning that they’re designed to be quick and simple, for use when your emotions have already been triggered, and you may not have much time or mental capacity available. In addition to that, though, you should exercise before and after bouts of anxiety, and other troubling emotions. For example, I tend to encourage clients to challenge beliefs derived from the Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT) model of Albert Ellis, such as the following:

“Life MUST turn out how I want, otherwise it’s AWFUL.”

“People MUST approve of me, otherwise I’m WORTHLESS.”

“People MUST do what I want, otherwise they’re IDIOTS.”

“I MUST always succeed at what I do, otherwise I’m a FAILURE.”

“I MUST never feel anxious or upset otherwise it’s UNBEARABLE”, and so on.

Between times, when your emotions are not fully activated, you will have much more mental bandwidth available, which means you can actively dispute the underlying beliefs that cause your emotions, much more systematically and vigorously. For example, you may work on challenging your underlying beliefs in therapy or coaching sessions, or do so between sessions by completing a worksheet.

It’s a good idea to replace beliefs about unpleasant feelings being unbearable, which Ellis called “Low Frustration Tolerance” or “I-can’t-stand-it-itis”, with an attitude such as “I don’t like these feelings, but I can stand them.” That rational, flexible attitude toward will help you do the first A of AWARE by accepting your initial feelings. Certain ways of disputing the evidence for irrational beliefs can help you with the W of AWARE or watching thoughts in a detached manner, e.g., if asking “Where is this written in stone?” leads you to realize that your rigid rules, the SHOULDs and MUSTs, are subjective opinions not objective facts — they only exist in your head. Likewise, disputing beliefs about coping such as “I MUST seek reassurance whenever I feel upset" can help you with the second A and abandoning unhealthy emotion-driven behaviour.

You get back what you put into cognitive disputation. Challenging beliefs in writing can often make the ideas more memorable, precisely because it takes slightly more patience and effort. Keep challenging your core irrational beliefs from different angles — I can assure you there are lots of reasons why it’s irrational to rigidly demand things SHOULD be different that you don’t control, or that have already happened anyway. Persuade yourself that these are not facts but just subjective rules you’re imposing on yourself, or labels you’re attaching to people or events — it’s just a bunch of words you’re telling yourself at the end of the day. Changing your evaluative beliefs will, however, change your emotions to a greater extent than most people tend to assume.

Conclusion

Here’s a concrete example, for someone attempting to overcome anger in response to the perception that someone has insulted them.

A: Accepts the initial sensations and uncomfortable feelings, in this case feelings of emotional hurt that precede the anger, and sits with them for longer than normal, without responding. Initially, coaches himself through the process of coping with his feelings by instructing himself to “Slow down, pause”, etc. Practices affective labelling by telling himself: “I notice anger”, “Right now, I am clenching my jaw slightly”, etc. (Over time these self-instructions are faded, but the acceptance and self-awareness skills are maintained.)

W: Watches his thoughts from a detached perspective, e.g., notices thoughts such as “What a jerk!”, and “Why would anyone do that?” flashing through his mind. Also, notices that his unspoken attitude is “People MUST treat me with respect”, which he verbalizes to himself. Practices adopting a detached perspective by telling himself: “Right now, I am having the thought ‘What a jerk!’”, etc. (Again, this self-talk can be faded over time, as long as the skill of detachment remains.)

A: Acts in accord with his values, not acting out the anger. At first, he does nothing, but waits, rather than yelling or getting into an argument. He takes a time-out and excuses himself from the situation until he has regained his composure enough to respond rationally and assertively, in accord with the value he places on being wise and courageous.

R: During subsequent episodes, in addition to the preceding strategies, he begins repeating rational statements to himself, based on the disputation exercises he has been doing between sessions. For example, he tells himself, three times, “I don’t like it when people seem to disrespect me but I can handle it” or “I strongly prefer it when people treat me with respect but I don’t absolutely need them to do so; I can deal with it.” These rational coping statements replace the previous self-instructions. He repeats them as if he believes them 100% and tries to act accordingly.

E: Between episodes of anger he systematically challenges his irrational beliefs by disputing them in written exercises and in coaching sessions. He identifies irrational beliefs such as “People MUST respect me otherwise it’s AWFUL”, asking himself how this attitude can be realistic, rational, or helpful. He identifies rational alternative beliefs which can be turned into the brief rational coping statements above, for use during future episodes of anger.

Coping wisely with strong emotions, especially by using the skills above, will tend to weaken the underlying beliefs that predispose you to experience them. Likewise, challenging those beliefs between episodes, will tend to make it much easier for you to cope during episodes. In other words, there’s a reciprocal, or circular, relationship between proactive and reactive coping. By changing what you do between and during episodes of anxiety, sadness, or anger, you can create new habits and break the vicious cycle of unhealthy emotions.